I Become a Journeyman Taxi Driver

College and Spadina in 1970. Photo: Old Toronto

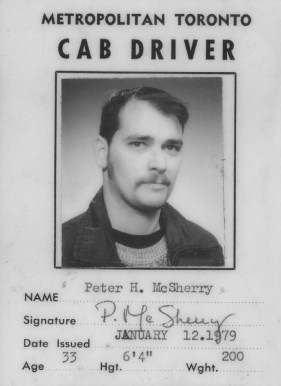

Taxi News is very grateful to Dundurn Press (Toronto) and the estate of Peter McSherry for giving us permission to re-publish excerpts of Peter’s book “Mean Streets.” We look forward to sharing the chapters “Me and the Owners” and “Me and the Dispatchers” with our readers, every Saturday.

Click here to read Section #1 “My Beginning as a Taxi Driver”

***

My real career in the taxi business began in the summer of 1973, after I saw a sign on a passing taxicab that read “Taxi drivers wanted,” and said to see “Mr. Dilby” at such-and-such an address. In presenting myself at Mr. Dilby’s loft office, I started down a trail that has stretched out over thirty years — and will continue until the end of my working life, though I will likely not work in the future on a full-time basis. At this juncture, I am, irretrievably, a cabby.

Dilby was the first of several small fleet operators whom I would work for during the next twelve or thirteen years. All had between five and eight cars operating out of what I’ll call the “Foobler Taxi Company,” a large city-wide brokerage. None kept a regular full-time mechanic, as the 442 Garage and the 478 Garage had done, but instead sent their equipment out to be fixed. This often meant that real maintenance happened only in a crisis — after something had gone really wrong.

Though some of these small fleets were better than others, in retrospect it seems to me that the general pattern was that their taxicabs tended to be less well maintained than in the ideal fleet situation, which, in my experience, is where the fleet operator actually employs his own competent mechanic. At one of these less-than-ideal concerns, maintenance was a very low priority, to the extent that the cars seemed virtually held together with string and sealing wax. What I was doing “working for” this fellow I can’t now fathom at all.

According to the later comment of a relative-by-marriage, Dilby was “a tough man in business,” which I’d estimate to be putting it mildly. For a twenty-eight-year-old boy from the Avenue Road hill district, who had read a lot of books but who wasn’t too smart in terms of the School of Hard Knocks, Dilby was nothing less than an education. If there were any loose nickels around, Dilby wanted them. The weak and defenseless, Dilby sheared like sheep. It was a full-time job just keeping his hand out of your pocket. He had skimming his inexperienced drivers down to an art form.

I remember, in an early business dispute with Dilby, making some stupid preposterous argument designed to appeal to his non-existent sense of liberal morality. “You’re such a nice boy, Peter,” Dilby spat at me with considerable bitterness — and, even then, I knew why.

Dilby had a number tattooed on his arm and deep welts across his back where, in childhood, he had been the victim of an abomination of a kind that, having been well-born in this soft, rich country, I could never really know or comprehend. He was a Holocaust camp survivor. He wasn’t giving any free rides in life to the likes of me, and, even as it happened, I knew in my mind that I had to cut him some slack. After I learned to neutralize the worst of his antics, I came to regard him as not such a bad guy at all. It was just that he had set up this little toll gate on life’s high- way — for people like me who had been dealt a better set of life’s cards and who weren’t quite smart enough to know that it was so.

The weak and defenseless, Dilby sheared like sheep.

That Christmas — Christmas 1973 — Dilby and I had an argument over the rental cost of my shift on Christmas Day. All of his other drivers were paying more than the regular shift rate (many years later, I can hardly believe this), but I was prepared to quit over the issue and, because of this, I “won,” whereas the other drivers “lost.” Afterwards, Dilby did something — it would take too much space to describe — that I have come to know meant that he was trying to help me learn a little lesson in life, and, in my memory, I am almost touched by it. In a sense, I think that he imagined that he was educating me, and, if it was so, he was right. It must have been that he actually liked me, for the lesson involved Dilby parting with a few bucks that he didn’t have to part with, and, in the normal run, that would have been excruciating pain for him.

Much later, in the early nineties, Mr. Dilby was ruthlessly murdered by a twisted young man whose motive was to steal a thirty-thousand-dollar ring that Dilby wore on one of his fingers. I was saddened to hear of this. In a fair world, which this one isn’t, Dilby deserved much better.

I handed Dilby his pink slip in 1976 or 1977 over a minor matter and took my working skills to a fleet operator I now think of as “Mr. Good Guy.” I was warned before going but paid no heed because Mr. Good Guy was “such a nice guy.” Very definitely, as I see it in retrospect, I was jumping from the fat into the fire. I was just too stupidly soft at the time to see what was coming.

Good Guy’s cars were not as good as Dilby’s, his idea of maintenance was ridiculous, and he was one of the cheapest and most selfish human beings I’ve ever met — certainly in the taxi business. I have little that’s good to say about the man. So I’ll write as little as possible.

The good thing about Mr. Good Guy was that he would sit and giggle in an egalitarian fashion with his drivers. Everything else about him was the bad thing.

Good Guy absolutely could not stand to see any of his cars sitting and would tolerate some of the worst garbage drivers and outright bums — some of whom owed him hundreds and even thousands of dollars for back shifts, accidents, and all sorts of shenanigans that no organized businessman would put up with. Good Guy actually catered to these clowns while taking full advantage of anybody else he could, especially any weakling or anyone who was too soft or too honest. The guy was very good at using people and at finding people who could be used. Who needs such an owner? And why was I there? The answer is that there was something wrong with my self-concept at the time. I was exploitable and I was getting exploited. The Lord helps those who help themselves — and, even at this late stage of my life, I hadn’t yet fully grasped that this was so.

I can remember Good Guy getting away with pulling several “deals” on me. One happened in the wake of my being robbed by five guys at about midnight on a profitable Saturday night shift. I phoned my owner the following day and told him, “Mr. Good Guy, we got robbed last night.” I can still hear him bellowing into the phone, demanding his shift money anyway, claiming to believe that I had fabricated a robbery to deprive him.

Good Guy’s idea of fairness was for me to lose my float (about forty dollars, which was a lot of money in 1970), for me to pay for the taxi’s gas (perhaps fifteen dollars), for me to lose eight or nine hours of my working take (eighty dollars), and then I was to pay him the shift rental as well. He was to lose nothing. I am ashamed to admit that I lost the float, the gas, the money that I had earned, and I think I paid five or six dollars towards the shift. What I should have done was laugh in his face and quit on the spot, depriving him of an irreplaceable driver who, like few others, worked perhaps forty-five Sunday night shifts a year.

I had one other really nasty argument with Mr. Good Guy in an east-end garage after he had gone into — then suddenly dissolved — a partnership with a small fleet operator I’ll call “the Mastermind.” Ostensibly, in my mind at least, the argument was over generally poor maintenance of the cars I was renting from Good Guy, but he had the nerve to actually claim that, at some previous time, I had chiseled money out of him.

“You guys are all stealing from me,” was the sort of remark he passed as if I was to be included in whatever group he imagined would bother — presumably all of the taxi drivers he would so shrewdly sit around giggling with. The careful reader will note that this was the second such allegation I’d suffered from Good Guy, and, at this juncture, I demanded to know exactly when I had ever done any such thing. He couldn’t come up with a single instance, and neither could any other owner I’ve ever done business with.

“Then don’t ever say it,” I told Mr. Good Guy menacingly. He was smart enough to say nothing, and that was the last of our business life together. Already I was working more for the Mastermind than for Mr. Good Guy, so this last argument just finalized what was happening anyway.

The truth is that all of us had other interests, and we were more or less just ripping dollars out of the taxi industry.

This new guy and his son — “the Heir Apparent” — would become, over the years, friends of mine, but I have to write that, at times, I did have to forgive them a lot with regard to the maintenance of some of the cars that I was asked to drive. The truth is that all of us — the Mastermind, the Heir Apparent, and me too — had other interests, and we were more or less just ripping dollars out of the taxi industry.

After about two years I departed the Mastermind’s garage, not because of poor car maintenance, but as a consequence of a fairly vicious fight I had with his principal gas jockey. This fellow, whom I had always liked, held a grudge against me that I didn’t see coming, and, when I walked onto the Mastermind’s lot one afternoon, he suddenly got in my face in a threatening way. Trying to avoid trouble, I turned away from the guy two or three times, then I finally pushed him away, which caused him to attack me.

Then I made a mistake I’ll never make again.

Not thinking the guy could hurt me, I tried only to control my adversary’s attack and not to incapacitate him. In effect, I let him start fighting before I did — and I was very quickly on the ground and being kicked, or kneed, in the head. I thought to myself, okay, that’s it. I’m going to have to do this jerk, but, when I tried to get up, my left arm wouldn’t work. I didn’t know it, but I had a separated shoulder. The Mastermind and another fleet operator stopped the guy from pummelling me, and I got up. I said to him, “What the hell is this all about, Jack? I always liked you,” to which, with a premature victory smile, he responded, “I never liked you.”

“Okay, fine,” I said. “Let’s go.”

The rest of the fight was about four punches — me hitting my opponent in the head that many times with the only functioning arm that I had. I could see fear suddenly come into the guy’s eyes after the second or third wallop when he realized the mistake that he had made. In seconds, his nerve cracked and he abruptly quit fighting — and, in fact, he quit his job on the spot. He ran off the taxi lot claiming to be going for “an iron bar” — this was a fear/flight reaction — but, instead, he came back at the wheel of his car, purporting that he was going to run me over. At the risk of being labelled a coward, I stepped inside the office — as, indeed, he might have done it.

Both of us ceased working on the Mastermind’s lot that day. I suffered the humiliation of being forced onto welfare and, after my shoulder sufficiently healed, I trained especially hard at the YMCA with the fixed idea of “getting” this dope in an absolutely devastating way. Both the Mastermind and his son asked me not to do this, and I believe they suggested to this fellow that the smartest thing he could do was to get reasonable in a hurry on the first occasion he ran into me. Long before, I had spent five days in the Don Jail — serving time for a big whack of traffic tickets — and, while I had met some really interesting people in there, I didn’t figure I wanted to stick it out in “the bucket” for sixty or ninety days or however long I would have gotten for assault and battery. So I just decided to let the guy be reasonable and to let my little grudge go. It was the right thing to do, for, indeed, I am a very civilized person.

***

Next Saturday’s chapter: “I Finally Figure it Out.”

This excerpt is from Mean Streets by Peter McSherry and appears here by permission of Dundurn Press Limited and the estate of the Peter McSherry.

You can purchase copies of “Mean Streets” and Peter McSherry’s other books by visiting Dundurn Press or amazon.ca